Film Review: Dahomey

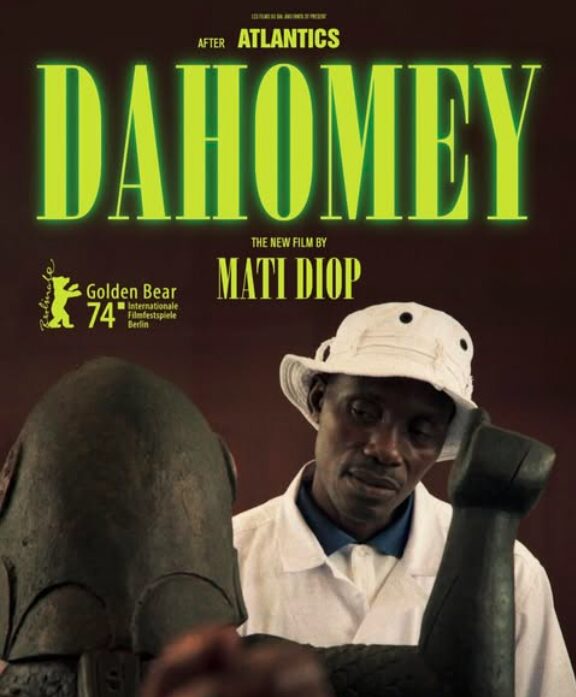

In Dahomey, French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop once again delivers a bold, meditative work that feels as much like a historical reckoning as it does a cinematic séance. Winner of the Golden Bear at the 2024 Berlinale, Dahomey is a haunting, elegiac documentary that confronts the long shadows of colonial theft—and the spiritual weight of return.

The film follows the repatriation of 26 royal artefacts looted by French colonial troops from the former Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin) in the 19th century. Diop begins with the objects themselves—thrones, statues, ceremonial treasures—finally uncrated after more than a century in French museums. But she isn’t interested in just documenting the return; she wants to explore what it means to bring these objects home.

What elevates Dahomey is its poetic voice. A fictionalized spirit of one of the artefacts narrates the film in a calm, ethereal tone—like a ghost observing the living. This choice pushes the documentary beyond exposition, turning it into a kind of cinematic libation. Through this narrative lens, Diop captures both the joy and discomfort of the return, particularly among the youth of Benin, who ask: is this enough? What now?

In Dahomey, French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop once again delivers a bold, meditative work that feels as much like a historical reckoning as it does a cinematic séance. Winner of the Golden Bear at the 2024 Berlinale, Dahomey is a haunting, elegiac documentary that confronts the long shadows of colonial theft—and the spiritual weight of return.

The film follows the repatriation of 26 royal artefacts looted by French colonial troops from the former Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin) in the 19th century. Diop begins with the objects themselves—thrones, statues, ceremonial treasures—finally uncrated after more than a century in French museums. But she isn’t interested in just documenting the return; she wants to explore what it means to bring these objects home.

What elevates Dahomey is its poetic voice. A fictionalized spirit of one of the artefacts narrates the film in a calm, ethereal tone—like a ghost observing the living. This choice pushes the documentary beyond exposition, turning it into a kind of cinematic libation. Through this narrative lens, Diop captures both the joy and discomfort of the return, particularly among the youth of Benin, who ask: is this enough? What now?

We see intimate moments with artists, students, and elders, each reflecting on identity, trauma, and the power of symbolic justice. Their reflections cut to the core of postcolonial tension—between pride in heritage and the brutal legacy of its disruption. One standout scene features university students debating the politics of restitution, underscoring that repatriation isn’t merely about artefacts but about power, memory, and sovereignty.

Visually, the film is stunning. Long, patient shots—of museum spaces, coastal rituals, and silent objects—are rendered with reverence. It’s as if the camera itself is bowing. Composer Wally Badarou’s score adds a quiet grandeur, never overwhelming, always guiding.

For African audiences—and especially Kenyans familiar with similar colonial legacies—Dahomey will resonate deeply. It asks what justice looks like when the harm spans centuries. It asks who gets to tell history, and who must carry it. Diop doesn’t pretend that return heals everything, but she creates space for reflection, mourning, and radical imagination.

Dahomey isn’t a conventional documentary. It’s a cinematic ritual, a whispered chant, a reclamation. And in the silence that lingers after the credits roll, it leaves us with a question: what else must be returned?

—

Dahomey is screening at Unseen Nairobi until May 31st.

Watch the trailer